Am I Feeling Depressed or Just Temporarily Down? A Practical Guide to Understanding Emotional Lows

Feeling depressed does not always point to a single cause or a clearly defined condition. Many people experience emotional lows and wonder whether what they are feeling is temporary or something that deserves closer attention.

This article organizes how “feeling depressed” is commonly understood outside of clinical diagnosis, how it may overlap with fatigue, lifestyle changes, and daily rhythm disruption, and why these states are often confused. Rather than offering conclusions or treatment advice, it focuses on practical ways people tend to observe their own emotional state and make sense of what is happening.

By examining commonly discussed factors, patterns, and decision points, this guide aims to support a calmer, more balanced understanding of emotional lows without rushing toward labels or assumptions.

Am I Feeling Depressed or Just Temporarily Down?

This question is often asked when emotional discomfort lingers longer than expected. In many cases, the feeling may not have a clear cause, which can make it difficult to determine whether it reflects a temporary emotional response or something that requires closer attention. This section aims to clarify how the phrase “feeling depressed” is commonly understood in everyday contexts, without making clinical judgments or diagnoses.

How “feeling depressed” is commonly understood outside of clinical diagnosis

Outside of medical or psychological settings, the term “feeling depressed” is frequently used to describe a broad range of emotional states. It may refer to low mood, lack of motivation, emotional heaviness, or a general sense of mental fatigue. In everyday conversation, this expression is often used without strict definitions, and its meaning tends to depend on personal experience and context.

Because of this, feeling depressed does not automatically indicate a medical condition. It is commonly understood as a subjective description of emotional discomfort rather than a formal assessment. This ambiguity is one reason why people may feel uncertain about how seriously to take their own emotional state.

Why temporary emotional lows and depressive states are often confused

Temporary emotional lows and longer-lasting depressive states can feel similar on the surface. Both may involve reduced energy, difficulty concentrating, or diminished interest in daily activities. The confusion often arises because emotional experiences are not easily measured by clear boundaries.

Short-term emotional lows are frequently influenced by identifiable factors such as stress, fatigue, or situational changes, and they may ease with rest or time. In contrast, depressive states are often discussed in relation to persistence and impact on daily functioning. However, without clear markers, many people find it difficult to distinguish between the two, leading to understandable uncertainty.

What Does “Feeling Depressed” Usually Refer To?

In everyday language, “feeling depressed” is commonly used to describe a state in which emotional balance feels disrupted. It does not point to a single condition, but rather to a collection of experiences that affect how a person feels, thinks, and moves through daily life. This section outlines how the term is generally understood outside of clinical frameworks.

How mood, motivation, and daily functioning are typically affected

When people describe themselves as feeling depressed, they are often referring to changes in mood, motivation, and everyday functioning. Mood may feel persistently low or heavy, even without a clear trigger. Motivation can decrease, making it harder to start or sustain routine activities. Tasks that once felt manageable may require more effort or feel emotionally draining.

In daily life, this can appear as reduced engagement with work, social interaction, or personal interests. The key point is not the presence of a single symptom, but how multiple small changes overlap and alter the overall rhythm of the day. These shifts are often subtle, which is why they may be difficult to articulate clearly.

Why individual experience varies widely in duration and intensity

Experiences described as “feeling depressed” differ significantly from person to person. For some, the state may last only a short period and ease as circumstances change. For others, similar feelings may persist longer or fluctuate in intensity over time. This variation is influenced by personal sensitivity, environment, stress levels, and physical condition.

Because of these differences, there is no universal timeline or intensity that defines the experience. What feels overwhelming for one person may feel manageable for another. This wide range is one reason the term remains ambiguous and why comparisons between individuals are often unhelpful.

Where the Boundary Lies Between Fatigue and Depressive Feelings

Fatigue and depressive feelings are often discussed together because they can appear similar on the surface. Both may involve low energy, reduced motivation, and a sense of heaviness. However, they are not always the same state. Understanding how people commonly distinguish between them can help clarify what is happening without forcing a diagnosis.

How rest and recovery often affect temporary emotional exhaustion

Temporary emotional exhaustion is frequently linked to physical or mental overuse. Long work hours, lack of sleep, or sustained stress can drain emotional capacity, making everything feel harder than usual. In these cases, rest and recovery often lead to noticeable improvement.

After sufficient sleep, reduced stimulation, or a short break from pressure, mood and motivation may gradually return. This pattern, where recovery follows rest, is commonly used as a practical reference point for understanding fatigue-related low mood. The key feature is that emotional heaviness tends to ease as the body regains balance.

When low mood may persist despite adequate rest

In contrast, there are situations where low mood does not improve even after rest seems adequate. Sleep may be sufficient, daily demands may be reduced, yet emotional heaviness or lack of interest continues. This persistence often raises questions about whether something beyond simple fatigue is involved.

Rather than pointing to a single cause, this pattern is usually described as a signal to pause and observe more closely. The absence of improvement after rest does not automatically define a condition, but it can indicate that emotional strain is layered with other factors, such as ongoing stress or environmental pressure.

How Long Feeling Depressed Is Often Considered a Signal to Pause and Reflect

The length of time someone feels depressed is often discussed as a reference point, but not as a strict rule. Rather than serving as a clear boundary, duration is commonly treated as a signal to slow down and reflect on how one’s emotional state is interacting with daily life.

Why duration alone is not a fixed diagnostic threshold

There is no universally agreed number of days that automatically separates temporary low mood from a more serious condition. Emotional states do not progress in uniform timelines, and people recover at different speeds depending on context, support, and personal resilience.

Because of this variability, duration is usually framed as contextual information rather than a definition. Feeling low for a certain length of time does not, by itself, determine meaning or severity. The same timeframe can represent very different situations depending on what else is happening in a person’s life.

How daily life impact is commonly used as a practical reference point

Instead of focusing only on how long low mood lasts, many discussions emphasize how much it interferes with everyday life. Changes in sleep, appetite, concentration, or the ability to carry out routine tasks are often used as practical reference points.

When emotional heaviness begins to limit daily functioning, even in small ways, it may be treated as a cue to pause and reassess. This approach prioritizes lived impact over abstract timelines, allowing people to observe their condition without immediately labeling it.

What Factors Are Commonly Associated With Feeling Depressed

Feeling depressed is often discussed as the result of multiple overlapping influences rather than a single identifiable cause. Many observations suggest that emotional strain tends to emerge when everyday conditions quietly accumulate, making it difficult to point to one clear trigger.

How environment, sleep, and ongoing stress may overlap

Environment, sleep quality, and ongoing stress are frequently mentioned together because they tend to influence each other. Changes in living conditions, work pressure, or social surroundings may gradually increase mental load, especially when rest and recovery are insufficient.

Sleep disruption is often described as both a cause and a consequence of low mood. When stress interferes with sleep, emotional resilience may weaken, which can in turn make daily challenges feel heavier than usual. This overlap makes it difficult to separate one factor from another.

Why emotional strain is rarely caused by a single factor

Emotional strain is rarely traced back to a single event or condition. Instead, it is commonly understood as the outcome of layered pressures, including physical fatigue, psychological stress, and situational uncertainty.

Because these factors interact, focusing on one cause alone may overlook the broader context. Recognizing emotional strain as a combination of influences allows for a more flexible and less self-blaming perspective, making it easier to reflect without forcing a simple explanation.

What Factors Are Commonly Associated With Feeling Depressed

Feeling depressed is often discussed as the result of multiple overlapping influences rather than a single identifiable cause. Many observations suggest that emotional strain tends to emerge when everyday conditions quietly accumulate, making it difficult to point to one clear trigger.

How environment, sleep, and ongoing stress may overlap

Environment, sleep quality, and ongoing stress are frequently mentioned together because they tend to influence each other. Changes in living conditions, work pressure, or social surroundings may gradually increase mental load, especially when rest and recovery are insufficient.

Sleep disruption is often described as both a cause and a consequence of low mood. When stress interferes with sleep, emotional resilience may weaken, which can in turn make daily challenges feel heavier than usual. This overlap makes it difficult to separate one factor from another.

Why emotional strain is rarely caused by a single factor

Emotional strain is rarely traced back to a single event or condition. Instead, it is commonly understood as the outcome of layered pressures, including physical fatigue, psychological stress, and situational uncertainty.

Because these factors interact, focusing on one cause alone may overlook the broader context. Recognizing emotional strain as a combination of influences allows for a more flexible and less self-blaming perspective, making it easier to reflect without forcing a simple explanation.

Why Travel, Relocation, and Lifestyle Changes Can Trigger Low Mood

Travel, relocation, and lifestyle changes are often associated with excitement or opportunity, but they can also coincide with subtle emotional strain. Even when changes are voluntary or positive, the loss of familiar structure may quietly affect emotional stability.

Rather than being caused by the change itself, low mood is often described as emerging during the adjustment process that follows physical movement or lifestyle shifts.

How unfamiliar environments may increase mental load

Unfamiliar environments require continuous processing of new information. Language, social cues, transportation systems, and daily routines all demand conscious attention when they are no longer automatic.

This sustained mental load may reduce the capacity to regulate emotions, especially when rest and recovery are insufficient. What feels manageable at first can gradually become tiring, making low mood more noticeable over time.

Why emotional adjustment sometimes lags behind physical movement

Physical relocation happens immediately, but emotional adjustment often unfolds more slowly. The mind may still rely on previous reference points while the surrounding environment has already changed.

This time gap can create a sense of disconnection or instability, where a person appears settled externally but feels unsettled internally. Such lag is commonly described as a normal part of adapting to change, rather than a sign that something is wrong.

Why Travel, Relocation, and Lifestyle Changes Can Trigger Low Mood

Travel, relocation, and lifestyle changes are often associated with excitement or opportunity, but they can also coincide with subtle emotional strain. Even when changes are voluntary or positive, the loss of familiar structure may quietly affect emotional stability.

Rather than being caused by the change itself, low mood is often described as emerging during the adjustment process that follows physical movement or lifestyle shifts.

How unfamiliar environments may increase mental load

Unfamiliar environments require continuous processing of new information. Language, social cues, transportation systems, and daily routines all demand conscious attention when they are no longer automatic.

This sustained mental load may reduce the capacity to regulate emotions, especially when rest and recovery are insufficient. What feels manageable at first can gradually become tiring, making low mood more noticeable over time.

Why emotional adjustment sometimes lags behind physical movement

Physical relocation happens immediately, but emotional adjustment often unfolds more slowly. The mind may still rely on previous reference points while the surrounding environment has already changed.

This time gap can create a sense of disconnection or instability, where a person appears settled externally but feels unsettled internally. Such lag is commonly described as a normal part of adapting to change, rather than a sign that something is wrong.

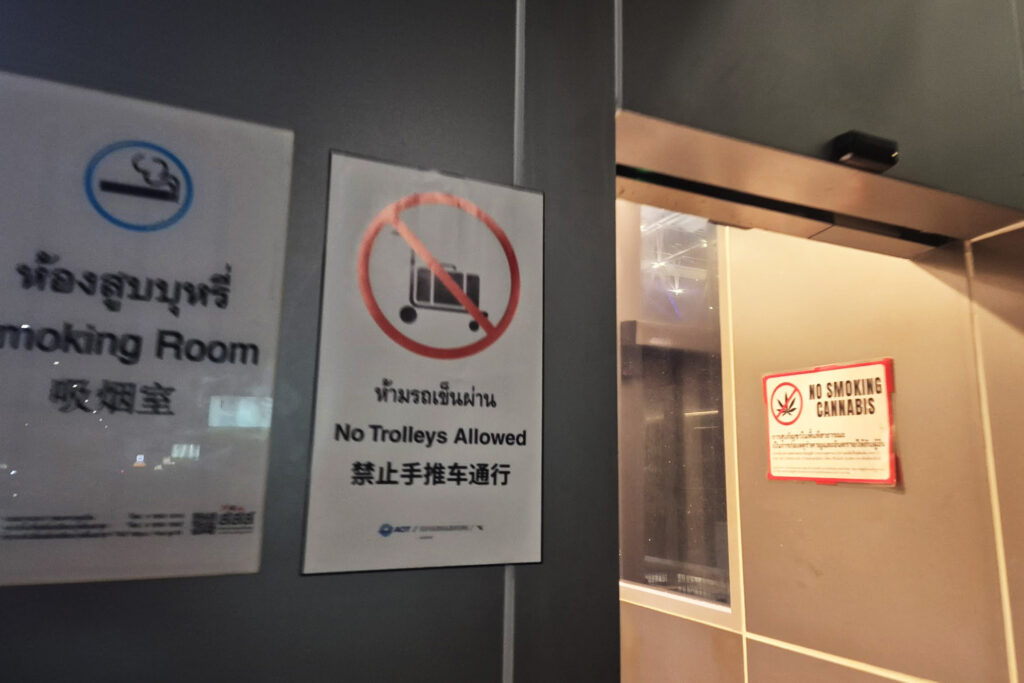

Can Medical Cannabis Affect Depressive Feelings?

Medical cannabis is sometimes discussed in relation to depressive feelings, but its impact is not described as uniform or predictable. Observations from both clinical discussions and everyday use suggest that responses may vary widely depending on context and individual condition.

Rather than being viewed as inherently helpful or harmful, medical cannabis is often framed as something whose effects depend on how, when, and by whom it is used.

Why effects may differ depending on timing and personal condition

The same product may feel different depending on emotional state, physical condition, and surrounding environment at the time of use. Fatigue, stress levels, and existing mood can influence how the experience is perceived.

This variability is why timing is often emphasized. Use during emotional instability may feel different from use during a relatively stable period, even if the dose and product remain the same.

How observation of one’s own response is commonly emphasized

Rather than focusing on generalized claims, many discussions highlight the importance of observing personal reactions over time. Paying attention to changes in mood, clarity, or discomfort after use is often described as a practical reference point.

Self-observation is commonly positioned as a way to avoid over-attributing cause or benefit. If an experience feels uncomfortable or unhelpful, pausing or reassessing is often mentioned as part of a cautious approach.

How to Think About Cannabis Use When Feeling Emotionally Unstable

When emotional state feels unstable, cannabis use is often discussed with an emphasis on caution rather than optimization. Instead of asking whether it will help or worsen the situation, many perspectives focus on how to approach use without increasing emotional load.

In this context, cannabis is not framed as a solution, but as a variable that may interact with an already sensitive mental state.

Why caution and self-monitoring are often suggested

Emotional instability can make internal changes harder to interpret clearly. Subtle shifts in mood, anxiety, or thought patterns may feel amplified, making it difficult to separate the original emotional state from the effects of cannabis.

For this reason, caution is often recommended as a way to preserve clarity. Monitoring how one feels before and after use is commonly described as more important than the amount or method itself.

How distancing or pausing use can be part of self-assessment

In some discussions, choosing to pause or create distance from cannabis is framed not as avoidance, but as a form of observation. Stepping back can make it easier to notice baseline emotional patterns without additional variables.

This pause is often positioned as temporary and intentional. Rather than a judgment about cannabis itself, it is treated as a way to better understand one’s current condition and needs.

How Information Searching Can Increase or Reduce Emotional Stress

When people begin to feel emotionally unsettled, searching for information is often one of the first responses. Information can provide reassurance, but it can also increase stress depending on how it is consumed and interpreted.

In many discussions, the issue is not whether information is good or bad, but how much is taken in and how closely it is applied to one’s own state.

Why excessive searching may amplify worry

Repeatedly searching for explanations or labels can sometimes lead to heightened anxiety. As more information is consumed, attention may shift from understanding to constant comparison, especially when symptoms or experiences do not align perfectly.

This pattern is often described as reinforcing uncertainty rather than resolving it. Instead of offering clarity, excessive searching may create a sense that something is wrong or unresolved, even when the situation has not changed.

How to keep information at a helpful distance

Keeping information at a helpful distance is commonly described as treating it as reference material rather than a conclusion. Reading with the intention of learning, rather than self-judging, can reduce emotional load.

This approach emphasizes selective intake and intentional pauses. By limiting how much information is consumed at one time and avoiding constant rechecking, information can remain supportive instead of overwhelming.

What Can Be Done on Days When You Feel Depressed

On days when emotional heaviness is noticeable, doing “something productive” can feel unrealistic. In many discussions, the focus shifts away from solving the situation and toward preventing further strain.

Rather than aiming for improvement, these days are often framed as moments to avoid making things harder for oneself.

Why small, low-effort actions are often prioritized

Small, low-effort actions are commonly emphasized because they place minimal demand on mental and physical energy. Actions such as basic self-care or maintaining a simple routine are often described as more sustainable during emotionally low periods.

This approach is based on reducing friction rather than achieving progress. By choosing actions that feel manageable, people may avoid additional feelings of failure or exhaustion.

How not forcing positivity can reduce pressure

Forcing positive thinking or motivation is often described as counterproductive when emotional capacity is low. Trying to “feel better” too quickly may create internal pressure and frustration.

Allowing neutral or flat emotional states is sometimes seen as a form of relief. By not demanding optimism, individuals may experience less resistance and a gentler emotional baseline.

How Environment and Human Connection Can Support Emotional Stability

Emotional stability is often discussed not only as an internal state, but as something shaped by external conditions. When mood feels fragile, surroundings and human connection may play a larger role than personal effort or mindset.

Rather than trying to change feelings directly, adjusting where and with whom time is spent is commonly described as a practical support layer.

Why safe spaces and trusted people are often highlighted

Safe spaces and trusted people are frequently emphasized because they reduce the need for emotional defense. In environments where judgment or performance is expected, emotional strain may increase even without obvious conflict.

Being around people who do not require explanation or justification is often described as stabilizing. Trust allows individuals to remain quiet, low-energy, or emotionally neutral without pressure to “be okay.”

How adjusting surroundings may ease emotional load

Changes to surroundings are often framed as a way to lower background stress rather than solve emotional issues. Lighting, noise levels, crowd density, and familiarity are commonly mentioned factors.

Small environmental adjustments may reduce constant stimulation, which can make emotional processing feel less overwhelming. In this sense, space is treated as an indirect but meaningful influence on emotional balance.

How Sleep, Nutrition, and Movement Are Commonly Related to Mood

Sleep, nutrition, and movement are often discussed as background factors that influence mood rather than direct causes of emotional states. When emotional balance feels unstable, these elements are commonly reviewed not as solutions, but as conditions that can either support or strain mental stability.

Rather than aiming for optimization, many discussions focus on whether these basics are placing unnecessary pressure on the body and mind.

Why balance matters more than ideal routines

Balance is frequently emphasized over ideal routines because strict rules can become an additional source of stress. Perfect sleep schedules, ideal diets, or fixed exercise plans may feel unattainable when emotional energy is low.

Maintaining a level that feels sustainable is often described as more supportive than chasing “best practices.” Small irregularities are generally seen as less harmful than the stress created by forcing consistency.

How gradual adjustment is often recommended

Gradual adjustment is commonly suggested because sudden changes may overload both physical and emotional systems. Shifting sleep times, meal patterns, or activity levels too quickly can create discomfort that outweighs potential benefits.

Incremental changes allow observation without pressure, making it easier to notice how the body and mood respond. This approach treats daily habits as flexible supports rather than strict requirements.

How to Hold a Balanced Perspective When Feeling Depressed

When feeling depressed, perspective often narrows, making thoughts feel more absolute than they may actually be. In these moments, maintaining balance is less about finding answers and more about preventing conclusions from becoming fixed too quickly.

Rather than deciding what the feeling “means,” this perspective focuses on allowing uncertainty and keeping multiple interpretations open.

Why avoiding quick conclusions can protect mental well-being

Quick conclusions such as “this will not change” or “something is fundamentally wrong” are commonly associated with increased emotional strain. These interpretations may feel convincing during low mood, but they often form before enough information is available.

By delaying conclusions, emotional pressure may be reduced, allowing feelings to exist without immediately assigning meaning or outcome. This pause can help prevent temporary states from being treated as permanent conditions.

How acknowledging multiple coping paths may reduce isolation

Recognizing that there is no single correct way to cope can reduce the sense of isolation that often accompanies depressive feelings. When only one solution is imagined, failing to follow it may feel like personal inadequacy.

Acknowledging multiple possible coping paths allows flexibility, making it easier to relate to others’ experiences without comparison. This broader view supports the idea that emotional difficulty can be approached in different ways, depending on timing and personal context.